Believe it or not, the engineer who built the custom gas engine that powered the Wright brothers’ historic first flight in 1903 died almost penniless and nearly forgotten.

Charles Edward Taylor received little recognition for his contributions to aviation during his lifetime, but posthumously, he is known as a man of aviation “firsts” — including the first aviation mechanic, the first airport manager, and the first air disaster investigator.

Early life

Charles “Charlie” Taylor was born in 1868 and grew up in log cabin on a farm in Cerro Gordo, Illinois. After his family moved to Nebraska, Taylor quit school at the age of 12 and worked in the bindery of the Nebraska State Journal.

Taylor’s mechanical skills manifested early in life and after getting married, he landed in Dayton, Ohio, where he made farm equipment and bicycles. It was in Dayton that he met Wilbur and Orville Wright, who were renting a commercial space from Taylor’s uncle-in-law. Taylor had opened his machine shop by then, and the Wrights frequently brought him special projects for their bicycles.

As fate would have it, Taylor would sell his shop and eventually begin working in the Wright’s bicycle shop, making new parts and routine repairs. The first aviation-related project Taylor took on for the brothers was helping to build the wind tunnel they needed to conduct their glider experiments. But, the wind tunnel was hardly to be Taylor’s last collaboration with the Wrights.

Taking flight

Wilbur and Orville had advanced their plans for a powered airplane and knew the exact specifications of the gas engine they needed. When it came to who would build it, the job naturally fell into Taylor’s capable hands.

Taylor had only a basic knowledge of gasoline engines, but his giftedness in mechanics and design and his enthusiasm for the job prevailed. Working closely with the Wrights’ rudimentary sketches, within six weeks, Taylor had successfully built an engine capable of producing an impressive 12 horsepower.

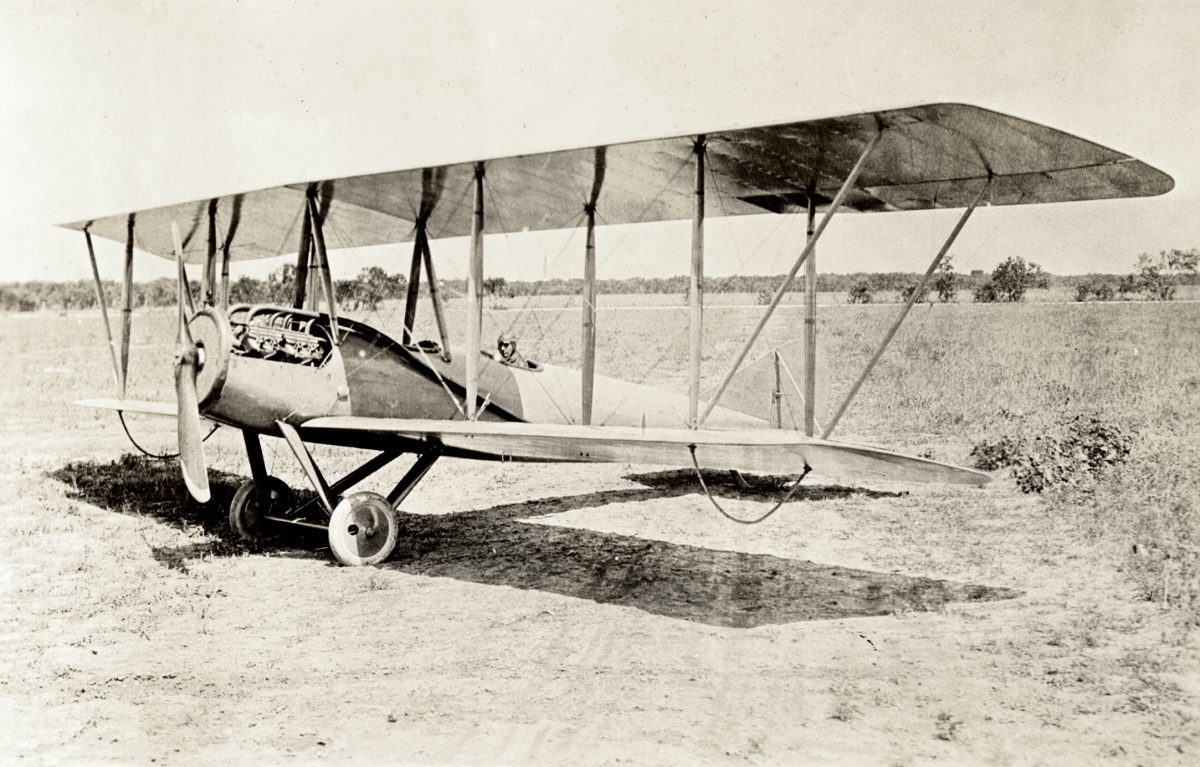

Taylor and the Wrights traveled to Kitty Hawk, North Carolina in 1903. On December 17, with a run of around 40 feet and a ground speed of 7 to 8 mph, the Flyer, carrying Orville, took off and remained in the air for approximately 12 seconds.

After the first successful powered flight, Taylor and the Wrights decided to return home and settle their flying operations in Dayton. They built a hangar on a 90-acre cow pasture, and Taylor maintained the field and the building, becoming the first “airport manager” in 1904.

In September of 1908, Taylor was scheduled to accompany Orville Wright on a demonstration flight for U.S. Army personnel. At the last minute, Army officers decided to include one of their own, a young West Point graduate from San Francisco. Tragedy struck when the aircraft crashed, seriously injuring Orville and killing the cadet.

Rushing to the scene, Taylor pulled out both men from the wreckage and watched as they were rushed to the hospital on stretchers. As later reported, Taylor leaned against the plane and began sobbing inconsolably. He eventually pulled himself together enough to take charge of hauling the wreck away so he could investigate further. Thus, Taylor became the first fatal air flight investigator.

Later years

Taylor continued to work with the Wrights until 1911, when he partnered with Calbraith Perry Rodgers, who wanted to make the first continental flight across the country. Following Rodgers across the country for 47 days, Taylor made hundreds of repairs to the aircraft, including clean-up after 16 crashes. The fact the airplane made it to its across-coast destination is a testament to Taylor’s advanced mechanic skills.

Taylor continued to work with the Wright brothers, helping to restore and preserve the 1903 Flyer for public exhibition. Later, Taylor moved from Ohio to California, and he and the Wrights eventually lost track. After a series of jobs, a failed machine shop, the Great Depression, and his wife’s death, Taylor’s life hit a downfall and his contributions to aviation eventually faded from most memories.

In 1945, Taylor suffered a heart attack, preventing him from working again. In 1955, he was discovered in the charity ward of Los Angeles General Hospital. Other than a small social security check and an $800 per year annuity that Orville had set up for him, Taylor was impoverished.

Fortunately, aviation enthusiasts rallied behind Taylor and raised the funds needed to move him to a private institution before his death in 1956. He was 88 years old, the last living of the three men who invented the first successful airplane. As the National Aviation Hall of Fame notes, Taylor “never sought noteriety from his work with the Wrights and few ever recognized his contributions. He was never in touch with the important aviation personages nor was he ever invited to attend any of the big celebrations held in honor of the Wrights.”

Taylor is buried in the Portal of Folded Wings Mausoleum in Burbank, CA, which is dedicated to aviation pioneers. While Taylor was not formally recognized for his well-deserved aviation achievements during his lifetime, his legacy has since been acknowledged with:

A special salute to Charlie Taylor and all aviation mechanics who keep our wings in the sky!