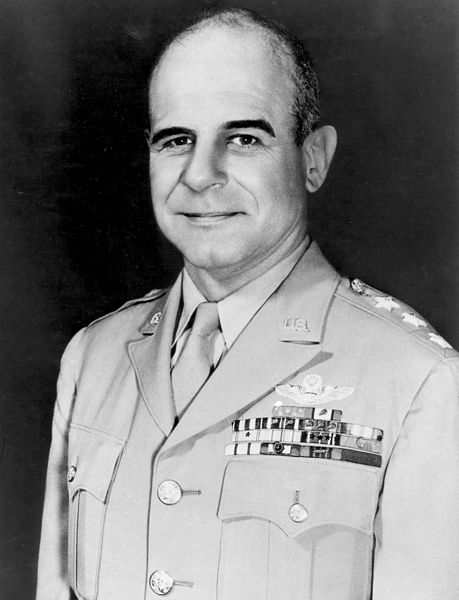

In the first of our series about aviation pioneers, this spotlight is on Jimmy Dolittle, who was key in the development of instrument flying. It may seem shocking now, but flying through darkness and inclement weather once relied entirely on a pilot’s sense of motion, which as we know can become disoriented, especially with few to no landscape or terrain cues visable from the cockpit.

Dolittle was born in 1896, and spent his early years growing up in the remote town of Nome, Alaska. He saw his first airplane in 1910. Aviation inspired him; he left college in California in 1917 and enlisted at the School of Military Aeronautics. He received his flight training at Rockwell field in California and was commissioned as a second Lieutenant in the U.S. army in 1918.

While he spent much of World War I as a flight instructor based in the U.S., he served so well as a flight leader and gunnery instructor that he was retained in the Air Service after demobilization. His interest in what would become the avionics field most likely emerged in 1921, when he attended the Air Service Mechanical School at Kelly Field and took an Aeronautical Engineering Course. Flying a de Havilland DH-4, he made the first cross-country flight. The de Havilland DH-4 sported early instruments that aided in navigation, and he was able to fly safely from Florida to San Diego in 21 hours and 19 minutes, with only one stop to refuel.

Dolittle served as a test pilot and aeronautical engineer for several years during the interwar period where he operated out at McCook Field in Dayton, Ohio. He was both a practical pilot and an engineer, as he received his M.S. in Aeronautics from MIT in 1924 (the first ever issued in the U.S.!). This no doubt contributed to his later achievement of being the first ever to take off, fly, and land “blind” – using only his instruments to guide him.

This love of pioneering flight led Dolittle to participate in training in high-speed seaplanes. He attempted many speed records, and even won the 1925 Schneider Cup race. He was so dedicated that when conducting demonstration flights in Chile a year later, he once performed his aerial maneuvers after breaking both ankles! In addition to practical speed records, he was the first to prove it was possible to conduct aerial maneuvers like the outside loop – dropping from 10,000 feet at 280 miles hour and recovering into a complete loop.

Dolittle was handpicked to plan the first air raid on the Japanese in retaliation for Pearl Harbor. He would go on to be awarded four air medals for his service, as well as a Medal of Honor. He was also instrumental in changing U.S. fighter tactics, which assigned fighter pilots to clear a path ahead of bombers instead of sticking close by to escort them. This made it possible for the fighters to effectively target enemy planes well before they neared the bombers, and to break free of bombers after they had hit their targets in order to take on additional targets themselves.

The military and aviation were Dolittle’s life, and he remained active in that life after the war. He became the first president of the Air Force Association, which he helped create, and became a member of President Dwight Eisenhower’s President’s Board of Consultants on Foreign Intelligence Activities. In 1985, Doolittle was promoted to the rank of full 4-star General.

This aviation pioneer died at the age of 96 and was buried with honors in Arlington National Cemetery. Needless to say, all those who fly the skies owe him a debt of gratitude for making it that much easier to fly through the darkness on instruments alone, back into the light.