With cooler temperatures, lower density altitude, and beautiful views, fall is prime time for general aviation in many parts of the United States. But pilots aren’t the only ones flocking to the skies this time of year.

Each autumn, an average of 4 billion birds move south from Canada into the U.S. At the same time, another 4.7 billion birds migrate from the U.S. to the tropics. Therefore, the busy fall migration season presents serious safety hazards for pilots both on the ramp and in the skies.

Here’s what you should know about mitigating bird strikes:

Bird strikes have been a part of aviation since the very beginning. In fact, it’s believed that Wilbur Wright was the first pilot to encounter a bird strike in 1908.

More than 100,000 reports of bird and wildlife strikes have been reported over the past 20 years. However, experts think the total could be much higher because an estimated 80 percent of strikes go unreported by pilots.

According to the FAA, 97 percent of all wildlife strikes involve bird activity. In 2023 alone, pilots reported 19,603 bird strikes, an increase of 14 percent compared to the 17,205 strikes reported in 2022.

While birds rarely survive aviation encounters, such strikes can also cause major structural and engine damage to aircraft, sometimes resulting in serious or even fatal accidents.

Smaller birds such as mourning doves, killdeer, barn swallows, American kestrels, and horned larks are the most frequently identified species struck by civil aircraft overall. However, medium and large-sized birds such as ducks, Canadian geese, and turkey vultures tend to do the most damage to aircraft.

Between 1990 and 2023, the aircraft components most commonly reported as struck by birds were the nose, windshield, wing/rotor, fuselage, and engine. Aircraft engines are most frequently reported as being damaged by bird strikes, making up 25 percent of damaged components. In general, engines can ingest one or two small birds without failing, but there is no engine certified to ingest a large bird weighing over four pounds without shutting down.

The prevalence and danger of bird strikes are major reasons Hartzell Propeller works so hard to engineer carbon fiber composite propellers designed for maximum durability and longevity.

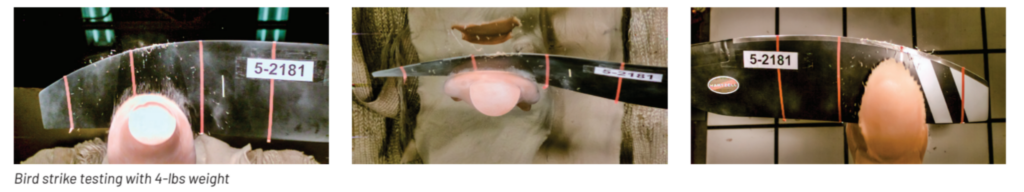

Our composite aircraft propellers feature aerospace-grade structural carbon fiber with a nickel-cobalt leading edge. Each and every new blade design is impact-tested to demonstrate the ability to tolerate bird strikes.

To date, Hartzell Propeller has conducted over 200 bird impact tests, a testament to our commitment to safety and reliability. We’ve even received photos and stories from pilots with Hartzell props that withstood large bird strikes and were still deemed airworthy, such as the gull strike pictured above.

Bird strikes can be unpredictable, but one of the best ways to prevent and avoid strike hazards is by staying informed and educated about bird and wildlife activity. Here are some facts to know:

If you have a close encounter with a bird or migrating flock, inform ATC right away so other pilots can be notified. If you are involved in a bird strike, remember that your first priority is to fly the aircraft. Many aircraft accidents occur when a pilot loses control of the aircraft in an attempt to avoid a bird. Once the aircraft is under control, you can assess any damage and communicate with ATC and the airport operators.

Whether or not your aircraft is damaged, it’s important to report the strike to the FAA by filling out the FAA Bird/Wildlife Strike Report. Your report will provide valuable information to aid the FAA’s ongoing wildlife strike research.

If possible, consider sending the bird strike remains to the Smithsonian Institute’s Feather ID Lab, which works to identify the bird species involved in a strike and support the FAA’s preventative efforts.

If you have questions about Hartzell’s carbon fiber composite propellers, we’re always happy to help. Get in touch with our team here.